From gruelling border crossings to helping fold a massive pile of laundry, there seems to be nothing Tanya Habjouqa won’t do to document the gender, social and human rights issues she specialises in. Some mojo and taking the time to ensure her subjects are utterly relaxed also help the half-Texan, half-Jordanian photographer snap those out-of-the-ordinary photos.

As well as work that has been exhibited worldwide, Habjouqa, qualified in journalism and anthropology with an MA in Global Media and emphasis on Middle East Politics from SOAS, University of London, is mostly known for “Occupied Pleasures.” The project-turned-book is a testimony to Palestinian resilience. Habjouqa focuses on simple daily pleasures, nuggets of happiness and humorous or magical moments rather than the suffering while they live under the severe conditions of a prolonged occupation. Touted by “TIME” magazine and the Smithsonian as one of the best photo books of 2015, the labour of love earned the mother-of- two with a marital connection to Palestine a World Press Photo award in 2014.

We talk to Habjouqa, a NOOR member and founding member of Rawiya, which started as the first all female photo collective of the Middle East, about some of her most memorable moments while on assignment. We also ask the mentor to many about that picture perfect moment falling into place and taking part in Dubai’s SONY PhotoFriday, an event organised by Gulf Photo Plus as part of GPP Photo Week.

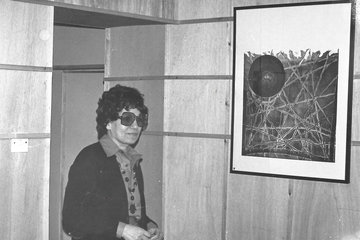

Tanya Habjouqa

Was there anything specific that made you want to become a photographer?

I think that writing and photography in many ways is one of the same, I look at photography as little short stories, little poems, I see it as text sometimes. And while I began as a writer, I think sometimes life pushes you in different directions. I took a year off from university, and while visiting Jordan I had an internship at “The Jordan Times,” doing long-form feature pieces. I had a little point and shoot camera, once in a blue moon they would let me shoot my own pictures and actually print them and that was thrilling. However, I began as a writer and writing is still pretty much a part of my photography. A good photograph should be able to stand on its own, think of it like a perfect black dress, it stands on its own, but when you pair it with an accessory, it becomes something else. There were times I could say a photograph compounded everything I wanted to, but I couldn’t in a longer essay.

Maybe I just didn’t know photography was an option, it wasn’t anything that was ever on the table. However, I recall one of the first gifts I got from my father was this little Kodak camera, this long, oblong funny little camera, and I think I was doing multi-media before it was even a thing. (Laughs) I swear as a little girl I would record audio of a play and then push the button and have the Barbies acting out the dialogue, and I would throw the Barbie down from the second storey and photograph it falling, just little games like that. I don’t know where it came from.

What sparked your interest in gender, social and human rights issues in the Middle East?

Gender, social issues and human rights are the crux of the Middle East, of our struggle, of what has changed, what needs to change. You access women and you access the entire society. I do find it a bit weary because women sell, especially women in hijab, right? And I think sometimes even in this region certain people will self-Orientalise themselves and play up the hijab. Unless they’re doing it from a critical perspective it gets a bit annoying because you know that it will sell. If you have a woman standing looking at the sea with her hair blowing in the wind versus a woman in a hijab standing by the sea, there’s something, you know, there’s this obsession with the hijab, right?

Plus, in general, women’s issues in the Middle East can be a bit reductive, the way they are misinterpreted or simplified, and sometimes good intent can cause harm, or sometimes it is even a bit more surreptitious than that. If you look at colonial history in the region and interventions as recent as the American occupation of Iraq, one of the rhetorics was about women’s rights under Saddam. While I’m no fan of Saddam, I’m no fan of what happened to that country afterwards. Of all the myriad of issues that existed, women’s rights were better in many ways than the surrounding countries. During the intervention, women’s rights weren’t at the top of the list but it was there, with NGOs coming etc.

In fact what followed from that foreign intervention was regression across the board. Again, when you access women, you access the entire society, the mothers, the daughters, the caretakers, the families and it was very telling. Not only did you suddenly have people talking about Sunni and Shi’ite, which did not exist before, people wouldn’t be asked that question, you also had areas in the south where women were being screamed at. I never forget, there was this little girl, she wasn’t even 12, and she just ran between houses to bring something to a neighbour. Then a man in a car screeched to a halt and jumped out and screamed at her for not wearing a hijab. What right did he have? She was traumatised and that would not have happened before.

As a woman I have a natural interest in women’s rights. I am a feminist, and I think when you touch on that issue, there’s a wider glean into society. One of my favourite quotes of all time, which I think puts the finger exactly on the pulse, is, “The opposite to patriarchy is not matriarchy but fraternity.” It’s also a good quote for people who misinterpret feminism.

Do you believe there is “chemistry” between photographers and their subjects?

Ideally, yes, I mean it’s magic, it’s alchemy when it happens. I call it mojo, like “Mojo Rising,” The Doors song. You have mojo beyond even just your subject, like when you’re looking for a story, when you’re on an assignment or just out and about. You have good mojo, bad mojo or no mojo. Of course, quite often it’s no mojo, you’re just driving and driving, you don’t have that aha click in your head or something bad happens, you have a negative experience or interaction. For example, somebody screams at you and won’t let you take a picture, but that’s the extreme, luckily that hasn’t happened.

Then there’s that mojo magic where everything falls into place for the perfect portrait, and you don’t even need to look in the camera if you’re shooting digital. You feel it; it’s this beautiful instinct where everything just fell into place. The light was perfect, but beyond that, it’s just the composition and the interaction between the two of you. It’s sync, it’s harmony, and it’s one of the most beautiful experiences you can ever have, and it does not happen all the time because really it’s something out of your hands. There are so many other factors at work to have that perfect moment fall into place.

How do you go about making your subjects relax and revealing a candid side to them?

It’s a fine line, it’s like every photographer has a different technique. A good friend of mine is over two metres tall, and I don’t know how someone can possibly not see him, but he has this Ninja-like quality where he can be in a room and you don’t notice him. Sometimes I’m envious about technique. My technique tends to be I connect, I give of myself and I get. It’s an interaction, but of course that doesn’t always work, you have to read the situation. If it’s someone who is by nature perhaps anti-social, dislikes the camera, I try the connection technique and if that doesn’t work, there are other ones, it’s not a copy, paste situation, it’s really case by case.

When possible, while working on an assignment that allows time and budget, or if it’s my own personal work, I won’t have my camera visible for one or two meetings. I just sit and talk, and I very much like their words to inspire the photograph. So I’ll be sitting in an interview, for example, casually looking around, no darting eyes syndrome as that makes people nervous. Then I start thinking in my head, OK, the interview has to be in the house because maybe they’re conservative and they don’t want to be seen being photographed, so it has to be in this room, look at that curtain, look at that wall. I kind of think about where a composition could happen while talking to them, and ideally they’ll tell a story, and it becomes collaborative. I’ll ask things like, ‘How can we illustrate this? What if we take a portrait? What do you think about this? What do you feel about that?’ Usually this way people relax, get excited and they’ll want to be in on it.

It’s case by case, with some people the tension isn’t going to go and you almost have to work with the tension, maybe that’s what you want to say, maybe that’s appropriate for the picture, it depends. It’s a nicely phrased question because the key is you get the person relaxed around you to the point where they can forget about you. So you’re there with the camera, talking to them and talking to someone else, and it’s totally relaxed and then when they forget about you, you can grab that perfect moment.

Tell us about some of the craziest things you did for your project, “Occupied Pleasures,” which turned into a book and merited you the World Press Photo award in 2014.

One of the craziest things I did was trying to get to Gaza from Egypt. Despite having a press card, the Israelis denied me access. It was quite fascinating, because I was lucky I had a friend, a Palestinian married to an Egyptian diplomat, and so I had wasta and I got permission. This was right when Morsi had taken over and it was a very volatile time, and I had this wasta to go in from Egypt to the Rafah border. It was very telling because I was in a position of privilege being treated badly. What did it mean for the myriad of Palestinians from Gaza?

Going in was one thing, but getting out I was sitting for hours, and after hours of waiting despite having all of the paperwork, I was livid. At this point I was only four and a half months pregnant but started simulating early signs of birth. I made such a big scene trying to get them to hurry up that they asked if I wanted to see a doctor. After the scene I had made I couldn’t say no, so I went to this back room and there were three or four men sitting in dirty white lab coats chain smoking. I looked at them and asked if there was a female doctor as an excuse to leave. I eventually got out, but it was very incredibly telling, it was also very exhausting to have to go from East Jerusalem to Jordan, to fly to Cairo and then drive from Cairo to the border. It seems ridiculous, but I knew the story would not be complete without telling that aspect.

It’s hard to say, I wouldn’t say crazy, because it was actually beautiful, it was just spending time with amazing characters and getting to know them. I think my new project, “The Unholy Land” is crazier, I’m hanging out in some pretty uncomfortable situations, with settlers, not just settlers but New Age people who want to build a new temple. I went to meet a woman who is a leader in the movement, a settler in The Mount of Olives. After chasing her for six months. I finally got an appointment, and when I showed up, she was frazzled and exhausted. I had to help her with the biggest pile of laundry I have ever seen, it was obscene; it was shocking. She had seven kids, and I had never seen clothes that poor and in this case it’s a chosen poverty because the material world doesn’t matter. That was pretty crazy and there’s the realisation of what you get to know from folding someone’s laundry!

You mentor young grantees from across the Arab region. What do you enjoy the most when it comes to teaching photography?

J. Kimery is a really unbelievable mover and shaker in the industry that has taught a lot of photographers with their workshops. I never knew I loved teaching until I started with The Arab Documentary Photography Program (ADPP), run in partnership with the Magnum Foundation and funded by The Arab Fund for Arts and Culture and Prince Claus Fund. It’s the only work I have ever had that I love as much as taking my own photography.

Then I started teaching at university one year after that, and I realised I do not enjoy teaching beginners, I’m not even remotely interested in someone who’s not serious. I want people who are obsessed and that’s what is so amazing about ADPP, they’ve already vetted those who are obsessed. I’ve met some of the most amazing photographers. It forces me to go out of the box as I critique them, they’re keeping me on my toes; it’s a mutual exchange. I get that same fusion of electricity, of creation, when I sync in with these students. I love the excitement, I love breaking out, going unexpected, going further. It’s just an amazing feeling. Since then I’ve gone on to teach in workshops in various situations and settings, and I think this is the best programme.

What was the most exciting aspect about taking part in SONY PhotoFriday?

What excites me is to see photography in the region growing, because I think we always had to look at France or New York. It wasn’t even supportive; it wasn’t even a career you could mention to your parents or extended family in the Middle East. Even to this day they say, ‘Oh wedding photographer,’ they don’t get it, there’s this dismissive element, when in fact photography is a deeply intellectual career. It takes an incredible amount of work to make it in this field, and to know what Hala (Salhi), (Mohamed) Somji and Gulf Photo Plus is doing to bring not only the workshops that have the technical skills to build you up, but actually other aspects of oddities and entities, these amazing ideas of how to push you further into a narrative. Usually you have to take in a number of workshops, or you have to invest in a very expensive degree. If you carefully select your workshops you could come out improving vastly.

I love the idea there are people innovating and pushing photography further, so it’s an honour to be part of that. Also, I got to see Somji, Hala and my best friend Tasneem (Alsultan) and the other photographers giving workshops. It was amazing and vibrant and it really makes me happy to see this happening in the region.